Introduction

We live and work inside systems that are far more complex than they appear on the surface. Conversations move quickly across users, revenue, features, prioritization, strategy, risk, and long-term vision—often within the same meeting. Decks are prepared, frameworks are referenced, thoughtful arguments are made. And yet, despite all that effort, there’s a familiar feeling that tends to follow: I think I understand this now.

That feeling rarely lasts. In the very next discussion, when the topic pivots slightly, the earlier clarity weakens. The subject is technically the same, but the angle has changed. What felt coherent a moment ago now feels incomplete. Not wrong—just insufficient. Over time, that pattern becomes hard to ignore.

This piece comes from sitting with that discomfort for a long time and trying to understand why clarity seemed so fragile in the face of complexity.

The Constant Wrestling and the Search for Something Abstract

This wasn’t about lack of effort. I spent hours preparing presentations, listening carefully, asking questions, and trying to connect dots. Many discussions were genuinely insightful. People weren’t confused, and decisions weren’t careless. Each conversation made sense on its own.

The problem was that understanding didn’t accumulate. It reset.

A discussion about users felt solid until it turned into a discussion about revenue. A feature debate felt resolved until governance entered the picture. Strategy conversations felt coherent until execution details surfaced. Each shift felt like starting again from a new altitude, even though we were circling the same system.

That led to a long period of searching—not for answers, but for better ways to look. Tools like Six Thinking Hats helped frame perspectives deliberately. Maslow’s pyramid lingered as a way to think about needs and motivation. My own writing over the last few years became a place to test and refine half-formed thoughts.

Each helped in fragments. None solved the core issue. What I was really looking for was a way to hold multiple viewpoints without losing orientation—a structure that could absorb pivots instead of collapsing under them.

Context, Asymmetry, and the Applied Lens

This section is the heart of the idea, so it’s worth slowing down here. The moment this abstraction settled for me came from a place far removed from business: testing.

As an engineer, the testing pyramid quietly shaped how I thought about quality. At the bottom were unit tests—many of them, fast, cheap, and easy to maintain. Above them sat integration tests—fewer, slower, and more brittle. At the top were end-to-end tests—expensive, fragile, and hard to debug, but still necessary. What made the pyramid powerful wasn’t just the categorization of test types. It was how clearly it showed asymmetry. As you moved upward, effort increased, fragility increased, and feedback slowed. At the same time, each layer clearly showed what it contained and what role it played.

Because the structure was fixed, you could reason about quality from different angles—speed, confidence, cost, risk—without losing your place. You weren’t redefining the system each time; you were applying a different lens to the same shape. That’s why the testing pyramid worked so well as a communication tool. It aligned teams without long explanations.

Much later, I realized the same idea applies elsewhere. Take user segmentation. If you arrange users as individuals, small companies, large organizations, and very large enterprises, the pyramid emerges naturally. Individuals form a broad base; very large enterprises sit at a narrow top. The shape captures asymmetry in scale.

From there, clarity comes when you apply one lens at a time. Apply user count, and the base dominates. Apply revenue, and value concentrates at the top. Apply needs, and simplicity gives way to coordination and governance. Apply complexity, and it steadily increases as you move upward. The structure stays the same; only the perspective changes.

This also explains why conversations often feel disorienting. When a discussion starts with revenue and someone introduces risk, it can feel like a derailment—unless both are being applied to the same underlying structure. With a fixed context, adding a new lens doesn’t break the conversation; it deepens it.

In abstract terms, this is what the Segmentation Pyramid enables. It fixes the context, makes asymmetry visible, and provides a stable surface on which different perspectives can be applied. The pyramid itself isn’t the insight. It’s what allows insights to appear without breaking coherence.

From Stumbling to Structure: Why the Pyramid Emerged

The pyramid didn’t arrive as a deliberate design choice. It emerged once segmentation and asymmetry were clear. When you arrange entities by scale—individuals, small groups, large organizations, institutions—you naturally get a broad base and a narrow top. The shape isn’t imposed; it reveals itself.

Looking back, the pyramid had been present in my thinking long before I noticed it. Physical pyramids exist because the shape works: a wide base, a narrowing top, stability through distribution. Maslow’s pyramid applied the same intuition to human needs. The testing pyramid did it for quality.

What connects these isn’t symbolism. It’s variance. A pyramid lets one variable change smoothly across layers. Look at count, and the base is large while the top is small. Look at complexity, and the direction flips—simple at the base, dense and constrained at the top. The same shape holds both readings.

Squares suggest uniformity. Stacks suggest equivalence. The pyramid makes difference visible. That’s why it became the natural container once the idea took shape.

Exploring Examples Across Functions (Tabular Views)

Ideally, each of the examples below would be drawn as a pyramid. For readability—and because I didn’t want to wrestle with ASCII triangles and text alignment—I’ve used tables instead. The shape stays the same in spirit; the format is just more forgiving.

Example 1: Understanding a Business Through Customer Segments

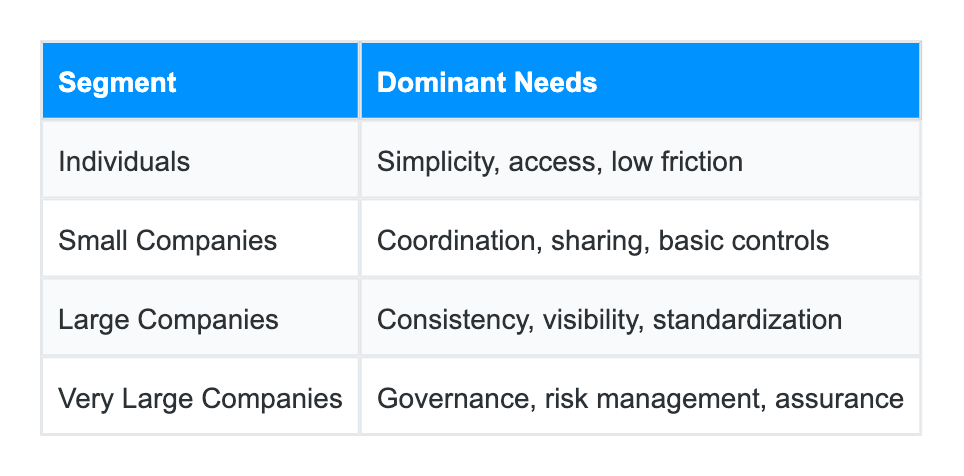

Lens: Customer Needs

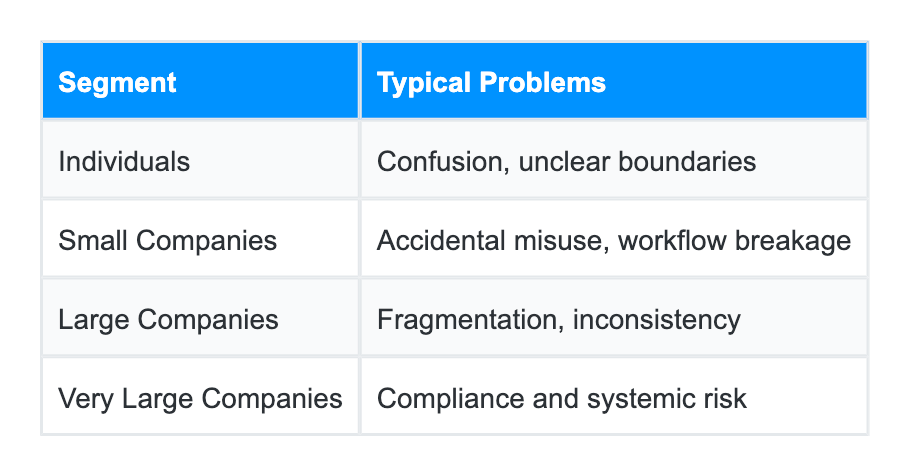

Lens: Problem Space

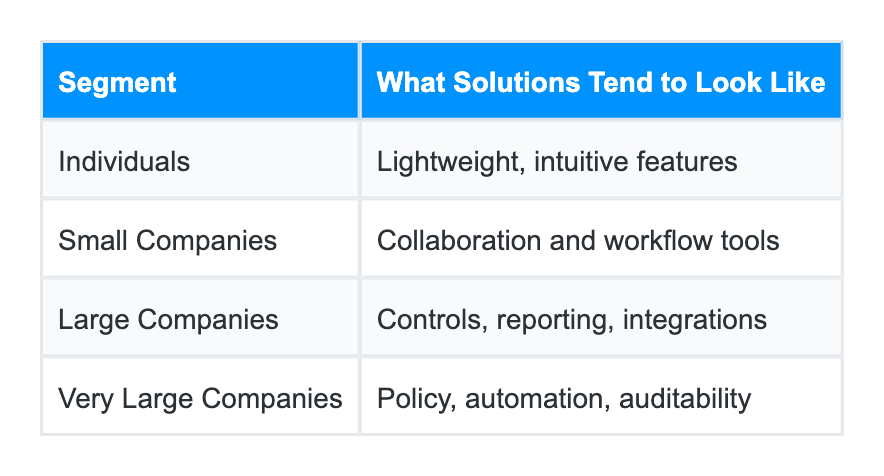

Lens: Solutions / Features

This framing alone explains why roadmap debates often feel circular: people are optimizing for different segments without saying so.

Example 2: Learning and Skill Development

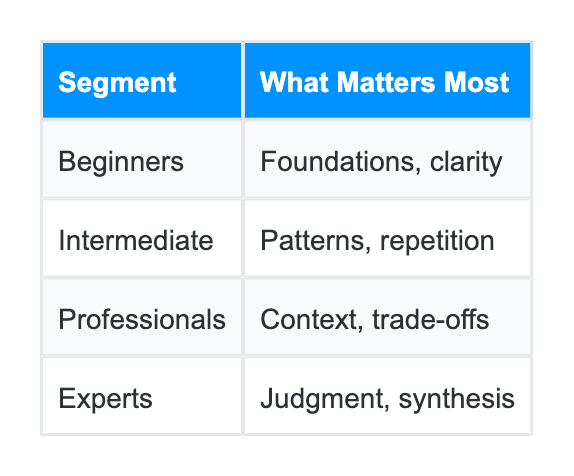

Lens: Learning Needs

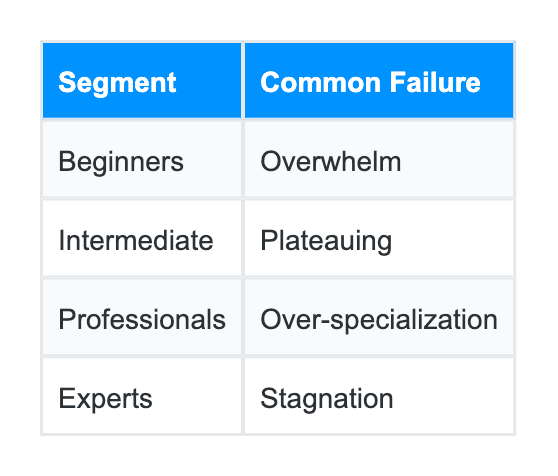

Lens: Failure Modes

Here, what looks like a content problem is often a segmentation mismatch.

Conclusion — Documenting a Thought in Motion

This isn’t a silver bullet, and it isn’t meant to be one. It’s simply a way of thinking that reduced some friction for me while dealing with complexity. Writing it down is less about fixing an answer and more about creating a reference point—something to return to, test, and refine.

In that sense, this is documentation for myself as much as for fellow journey persons. Capturing a thought allows it to be checked against experience and adjusted as needed. I also expect this lens to break in places—and that, too, will be useful.

For now, this is just a snapshot of a thought in motion, written down so it can evolve as new challenges appear.If you want, the next (and final) step can be a micro-polish pass—pure rhythm and word choice, no conceptual edits.